The Hundred Miles an Hour Baby

In 1930, George Eyston met Cecil Kimber for the first time. With the MG Factory’s support, Eyston was able to set the 5 kms, 5 miles, 10 kms, and 10 miles records at over 100mph in a 750cc MG Midget.

In 1930, George Eyston met Cecil Kimber for the first time. With the MG Factory’s support, Eyston was able to set the 5 kms, 5 miles, 10 kms, and 10 miles records at over 100mph in a 750cc MG Midget.

In his book “Flat Out”, he describes his runs at Montlhéry, France to set the records on February 16th, 1931.

Later he became well known for racing supercharged MGs. In 1938 he raised the land speed record to 357.5mph in his 2,000 hp Rolls Royce engined “Thunderbolt” at Bonneville.

George Eyston Gets a 750cc MG Midget to 100mph (from “Flat Out” first published in 1933).

“I ran into Jimmy Palmes by chance in the paddock at Brooklands when on a casual visit. He told me he was thinking of preparing a car for a 24-hours record which was at present held by the Austin at 64mph average, and this he would attempt with a standard M.G. Midget car converted from 847cc to 747 cc by reducing the cylinder bore with liners. He asked me whether I would like to co-operate in this attempt. He had already started work on the cylinder block and had the car at his works in Wimbledon.

“It seemed to me that this little M.G. car would be the best proposition of all, as I thought we stood a reasonable chance of hotting it up sufficiently to get some of the fast records at any rate. We would have resources behind us, and British at that. Instead of having a homemade job, we should have factory resources, because, as it turned out, Mr. Cecil Kimber, Managing Director of the M.G. Car Co., Ltd., Abingdon, gave his whole-hearted support to the proposal, and we went ahead preparing the car.

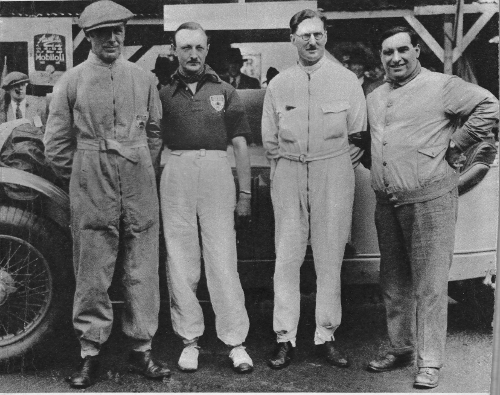

“I therefore gave up both the other projects, went over to Paris, paid what was due to Mr Ratier, and started on the M.G. venture. Palmes was just the man we wanted for the work of collaboration, as he was in close touch with the M.G. firm. Ernest and I paid numerous visits to Abingdon, and we found in Cecil Kimber, Mr. Charles, the chief of the Drawing Office, Mr. Propert, the General Manager, and Cousens and Jackson, of the Experimental Department, very willing cooperators. All went smoothly and the car in its unsupercharged form was ready for the track during the latter part of December 1930.

“It was shipped out to Montlhéry and given a final test, whereupon I started on a record attempt on December 31st.

“We succeeded in the unsupercharged form in taking the following records as a preliminary – 50 kilos at 86.38 mph; 50 miles at 87.11mph; 100 kilos at 87.30mph – which was most promising, and fully justified the confidence we had in the M.G. A piece came out of an exhaust valve, which stopped further running.

Now I had spent a great deal of time, together with colleagues, in perfecting a novel type of supercharger, which absorbed less power to drive than anything yet known. So the advent of this blower in its final form coincided with my desire to gain the distinction for M.G. of being the first baby car to record 100 miles an hour officially.

“I remember that a great many folk who should have known better were willing to bet that development had not reached this stage at present. But we took them on and won.

“I heard, however, that a very serious rival was in the field, so this made all of us think and act quickly. We took only four weeks to carry out the modifications, and everything was fitted up ready for shipment to Montlhéry again.

“On arrival the weather was awful – intensely cold, ice on the track, and sometimes deep snow. The cold was so intense in the garages under the track, which we had to inhabit that I wondered the mechanics could work under such arctic conditions.

“And the car gave trouble. For some reason, which it took a long time to discover, the car would only run a short distance and then stop. The ignition setting was perfect, and we could see nothing wrong with the mixture strength. But we were using alcohol fuel on account of the high compression pressure in the tiny engine, and it did not occur to us for some time that the extremely low temperature under which we were operating was the cause of this fuel freezing solid in the narrow passageways and jets of the carburettor. For this particular kind of fuel contains a certain percentage of water which keeps the motor cool, and this froze solid as the car rushed through the chilly air when approaching its maximum speed, with the perplexing result of an enforced engine stoppage on account of the lack of gas. The motor would cut right out. So the only thing to do, in the short time available, was to box the carburettor completely with the intake close up to the radiator, from which warm air could be drawn. It took a day or two to perfect the device, but in the end the trouble was conquered. The weather improved and the stage was set for an attempt on the 100mph speed mark.

“Conditions were by no means ideal. A strong wind with low clouds and threatening rain at any moment made the task pretty difficult. It was to be an entirely new experience for me, as previously I had never lapped the track at more than about 88mph with a baby, and the speeds I now contemplated were quite out of the ordinary.

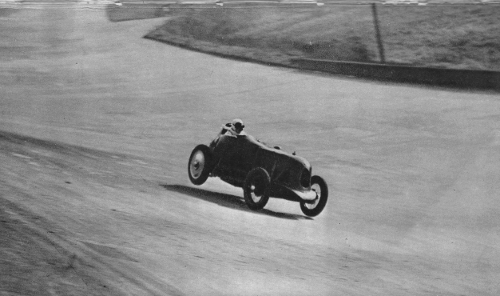

“We were out to get the records set up by the French “Grazide” car – records for distances of 5 kilometres, 5 miles, 10 kilometres, and 10 miles. To get all these in one run meant winding the car up to do a stretch of at least 15 miles at over 100mph.

“After a couple of laps to warm up the Midget to its work, I took a quarter-mile run at the ” tape ” and saw the revolution counter creep round to just where I wished it to be by calculations about 100 mph.

“I had never touched this speed before, even on a trial run, so I had a real thrill when I entered the timed stretch at 6,500 rpm. I simply put the car at the tape for all I knew. The Midget and I were off the straight and on to the slippery banking before one could say knife. Luckily I planted the car on the right spot, for as we tore round I had the sensation of being on a pair of gigantic roller skates, which wanted to climb higher and higher up the banking.

“Round into the wind we sailed, and I found it much easier than I had expected to hold a true course. Keeping up air pressure in the fuel tank needed continual attention. I had to twist myself to one side to reach the pump handle, but when I got hold of it I worked it for dear life; I was almost exhausted before the gauge registered the desired pressure, with the result that we had struck the far banking again and were half-way round it before I could wriggle myself back to the normal driving position. During that time the car did sundry slides and I was not feeling altogether too happy.

“Whenever I turned my head slightly to listen to the engine, it seemed to be emitting an unbroken high-pitched squeal from the exhaust, and every time I glanced at the revolution counter I found the needle dancing all over the dial. It was not its fault, since it was affected by the tremendous rear wheel spin due to the wet state of the track.

“Back down the straight and over the tapes once more. I had actually completed my first lap, but I wondered whether this had been at 100mph average or no.

“More pumping became necessary, and all round the banking I shoved and shoved at the pump handle, the car slewing about all over the place in consequence.

“As I crossed the tape for the third time I saw a steady 7,000 rpm on the counter, and knew, at last, that we were travelling!

“When I was signaled in I went straight up to the timekeepers’ box. As each result was “ground out ” and the announcement made that I had passed the 100 mark, we all had cause to remember February 16th, 1931.

“The run was quite successful, since all these records were taken at the following speeds:

5 kilometers – 103.13mph

5 miles – 102.76mph

10 kilometers – 102.43mph

10 miles – 101.86mph