MG Abingdon – A New Beginning Part 2

Well before the MGA was in production, John Thornley was exchanging correspondence with his Cowley director S.V. Smith about the suggestion that MG should look at the design of a ‘buzz-box’. This was intended to take the form of a small lightweight small-engined sports car.

Well before the MGA was in production, John Thornley was exchanging correspondence with his Cowley director S.V. Smith about the suggestion that MG should look at the design of a ‘buzz-box’. This was intended to take the form of a small lightweight small-engined sports car.

The whole idea was that it should be cheap and cheerful; somewhat along the lines of an up to date version of the M-type Midget that had been based on the original Morris Minor. Thornley was lukewarm about the possibility of producing such a vehicle.

Firstly, he felt that there would be limited demand for it in the United States, which he now regarded as MG’s premier market place, and secondly, what could it be based upon? It had been suggested that perhaps the current Minor could be used as a donor vehicle. The drawback with this was that although the wheelbase was some eight inches shorter than the MGA, the track was two to three inches wider. A further problem would be that only the floorpan could be carried over, still leaving a hefty bill for tooling up a new superstructure.

Finally, although the original Minor came with a zippy little overhead cam engine, the motor installed in the current vehicle left a great deal to be desired. A further difficulty that Thornley encountered was that however he approached the question of costs, he could not get anywhere near the bottom line that his directors were aiming for.

Word came through the grapevine that L.P. Lord and his deputy, George Harriman at Longbridge, perhaps frustrated by Abingdon’s lack of progress, had asked Donald Healey to investigate the ‘buzz-box’ concept. The Healey concern threw themselves into the project with the best of intentions. In spite of their best efforts however, the costs continued to increase. In due course Thornley and Enever were invited to Longbridge to view the prototype in the company of Harriman. Judging what they had seen to be a ‘brave try’, the Abingdon pair came away from the meeting with reservations regarding the strength of the rear suspension mounting points. They convinced themselves, however, that the car would be fully tested before being signed off for production.

Thornley was nevertheless skeptical about the Longbridge costings in spite of the fact that the hood and sidescreens were not included as standard equipment (can you see any manufacturer getting away with that today?)! Longbridge it would seem, using their pricing system, had arrived at a selling price of £528 including purchase tax. Thornley, using his own system, and taking the MGA as a reference, came up with an all-in price of well over £100 more.

Unabashed, Leonard Lord made the decision to put this new small sports car into production and henceforth it would be known as the Austin Healey Sprite. Once Longbridge had completed the engineering and determined the suppliers, the whole project was handed over to Abingdon. Seeing little difference between that first prototype and what had been released for production, Syd Enever decided to put one of the first cars off the line on a pave test at MIRA.

After only a short time on the test track his worst fears were confirmed. Not only was there a serious weakness in the rear underframe but visible creasing to the outer wing panel directly over the rear wheel arch. By this time the first 50 to 80 cars had gone down the production line. These then had to be sent back down the line again in reverse order with everything being removed until the cars became bare bodyshells once more. Meanwhile a repair kit of simple brackets had been developed (and tested) at Abingdon, which would resolve the problem. These were welded into the stripped shells on-site and handed over to the paint shop where they did their level best to make them look like new again. It was then back up the line to build them up into complete cars once more Pressed Steel were also reworking their stock of bodies with the same kit of parts until such time as they could bring in a more professional looking solution.

Happily the problem had been identified and resolved before any cars reached the public at large. One can only imagine the reputation the Sprite might have been saddled with had this not been the case! In point of fact the little Sprite captured the imagination of both the British and American public and Abingdon was hard pressed meeting the demand.

When not engaged with trying to fathom the mysteries of the BMC accounting system in order to demonstrate the profitability of his small factory (it must have had among the lowest overheads in the group), Thornley was devoting his thoughts to the future of the marque. For one thing he felt perhaps a little pessimistically that the public would begin to tire of the MGA after about three years. To this end he urged Syd Enever to start looking at a replacement without delay. Syd was also tasked to consider possible variations on the ‘A’: a four-seater perhaps, a cheap utility version and a facelift back end to provide more boot space. Whilst these ideas would eventually be left to wither on the vine there was another idea that Thornley was actively promoting.

This was to be a ‘super’ MGA which, he felt, would allow MG to break into the Porsche market, especially in America. He envisaged a version of the car having, of course, the twin cam engine, with disc brakes on the front wheels, a de Dion rear axle and upgraded interior trim featuring a smarter and more comprehensive instrument panel. Rebadged as the MGB, the aim would be to sell 50 of these per week in the US priced at just under $3,000 (still beating the Porsche price quite handsomely). It would also be made available in either Tourer, Coupe or Cabriolet versions. The company was well aware, however, that before such a car could be put on the market the engine would require a great deal more development (Thornley cited its preponderance to leak oil as one of its shortcomings).

By the time the car was launched in July 1958, after a fairly long gestation period, the whole thing had been watered down. Apart from the engine, the main difference to the standard car was the Dunlop disc brakes, rather surprisingly fitted to all four wheels, and the wheels themselves, being of the new Dunlop centre lock disc design that were much stronger (and easier to clean!) than the old Rudge Whitworth wire wheels. Gone were the de Dion rear end and the changes to the interior that John Thornley had envisaged. The marketing people had also killed off the idea of re-badging the car on the grounds that the changes were not sufficient to warrant it. Whilst the power unit gave generous amounts of horsepower (108bhp @ 6700rpm), its 9.9:1 compression ratio would prove to play a significant part in its downfall. In spite of assurances from the petrol companies to the contrary, the 100 octane fuel that was an absolute necessity for this engine was not universally available. The use of incorrect fuel could lead to engine failure in this rather highly-strung unit. Add to this the fact that even when it was running properly it still had a tendency to use more than its fair share of oil and one can see why the car began to get a reputation for being high maintenance, particularly in the United States. Despite literally dozens and dozens of modifications being introduced during its relatively short life, Engines Branch could not guarantee the one thing that was so desperately needed: reliability. Sadly, less than two years after its introduction, this exciting MG sports car that promised so much was withdrawn from production.

Towards the end of 1958 BMC decided to withdraw MG’s only saloon car, the ZB Magnette, from production in spite of the fact that it was still selling reasonably well. Although this would allow more space for the two-seaters, the real reason for its demise was the fact that there was a new Magnette in the pipeline. In fact the Corporation was about to launch its first complete range of BMC family saloon cars. These would be built at both Longbridge and Cowley around a single basic design, styled by Farina, which with mainly cosmetic changes would become either Austin, Morris, MG, Riley or Wolseley cars, all utilising the 1500cc B-series engine. The MG version, available from early 1959, was badged as the Magnette Mark III (presumably the ZA and ZB were counted as Marks I and II). This new Magnette was nevertheless well appointed if somewhat boxy in appearance with a particularly large overhang behind the rear wheels allowing the car to have the benefit of a cavernous boot. The biggest disappointment from the enthusiast’s point of view was the dropping of rack and pinion steering in favour of the rather old-fashioned cam and peg system so long preferred by Austin. The engine too was a bit of a let down. Whilst almost identical to that in the ZB it came with less rather than more brake horsepower. There was disappointment for the factory too, for although the car carried their name, they had for the first time ever, no say in either its design or manufacture.

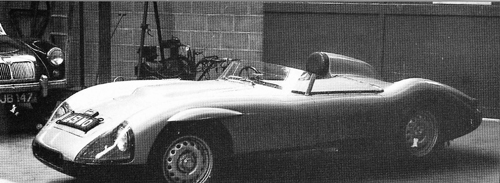

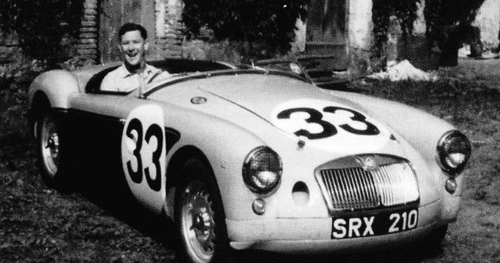

At the beginning of 1959 John Thornley was approached by a syndicate of members from the North-Western Centre of the MG Car Club, led by Ted Lund, requesting factory assistance regarding their intention of entering a Twin Cam at that year’s Le Mans 24 hour race. Always keen to see his cars do well in competition he came up with an exciting plan of action. Why not, he reasoned use EX186 for the purpose, the car that had originally been destined for the 1956 Le Mans race. Although there was still a blanket ban on Abingdon’s racing activities (except for exceptions such as Sebring which came within the jurisdiction of the Competitions Department), what harm would there be in a group of Car Club members entering the car off their own bat? Although the chassis still existed in the development department, having by this time acquired a de Dion rear axle, the body only existed as a full-scale drawing. By mid-May however, the sleek aluminium racing body, drawn up in 1955 by Jim O’Neill and his assistant Denis Williams, had become a reality courtesy of Midland Sheet Metal Ltd. Mated to its chassis frame, painted in two tone green, and fitted with a regulation Perspex windscreen, it looked every inch the racing car that had been intended. Sadly, with less than a month to go before the race, someone in the upper echelons of BMC had got wind of what was going on and threatened Thornley with dire consequences if he did not get rid of the car before any member of the public set eyes on it. Covered with a dust sheet and hidden in a dark corner of the shop it lay undisturbed for two years before being covertly smuggled over to Kjell Qvale, the importer of BMC cars in California and a good friend of John Thornley, who also had his own race shop.

A replacement Twin Cam was quickly found and prepared for the race by the boys in the development shop overseen by Henry Stone, who would, with Tommy Wellman, accompany the car to the circuit to act as mechanic for the duration of the event. During the race the car ran faultlessly for almost 20 hours when Colin Escott, who was driving at the time, had the great misfortune to hit a rather large dog that had wandered onto the course, whilst the MG was flat out on the Mulsanne straight. Considerable damage was caused to the front of the car, resulting in the air duct to the gearbox being blocked off. This in turn caused the gear oil to boil (also resulting in some rather nasty burns to the driver) and the car had to be withdrawn from the race as the result of a seized gearbox. Had it not been for this extremely rare incident it is almost certain that the car would have finished in a good position as only 13 cars finished the race out of a field of 62. Anyway, 20 hours at an average speed of 99.47mph: who said the Twin Cam was unreliable?

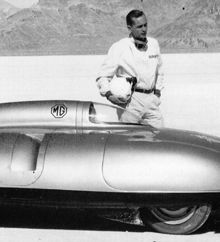

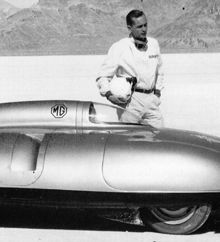

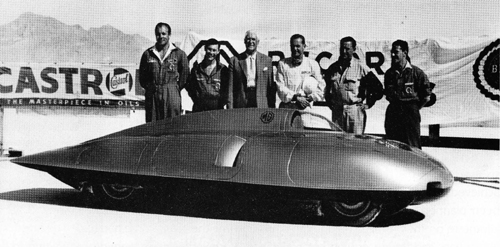

Meanwhile, for the formidable trio of Eyston, Thornley and Enever there was unfinished business on the Utah salt flats. Although the records set by MG in 1957 still stood, they desperately wanted to break through the 250mph barrier. EX181 would run this time in both the 1500cc and 2 litre classes. This would be achieved by running the car initially with the 1489cc supercharged engine fitted as in 1957, and then with another engine bored out to 1509cc. EX179 (in another guise) would also be going with them again. Don Hayter, who had joined Jim O’Neill’s body team in 1956, was handed a brief to create a new Sprite record car (EX219) using a production shell and grafting on an extended nose and tail to make it more aerodynamic. Unfortunately, due to the car’s short wheelbase and the need to fully enclose the front (and rear) wheels, the body shape did not perform that well in the wind tunnel. At that point the decision was therefore made to put the supercharged 948cc BMC A-series engine into EX179 and rather cheekily call it an Austin Healey Sprite!

As before, the plan was for Stirling Moss to drive EX181 with Phil Hill in reserve. For EX179 (or EX219 as it was now labeled), there would be three drivers: Tommy Wisdom, Gus Ehrman and Ed Leavens. These three drivers kicked off the proceedings by piloting the car around the 10 mile circle in three-hour stints for 12 hours, and in the process picked up nine international class G long distance records with no real dramas. With the sprint engine fitted, Gus Ehrman then proceeded to collect a further six records up to 1 hour. All of this had been achieved between September 9 and 11. lt had been planned to go for the flying mile and kilometre on the 14 mile straight line course as soon as the timing equipment could be set up, but at this point rain stopped play. The plan then was to break and resume in a couple of days. Then it rained again. This time it was a rainstorm of almost biblical proportions, which left the whole of the surface under almost half an inch of water. This may not seem much, but because of the high water table the only way to get rid of it was by evaporation. Their best guess at this point was that it would be at least another week before there could be any further running. This proved to be optimistic in the extreme, due in part to further rain, and it was not until the beginning of October that there was an opportunity to try again. By this time the programme had had to be drastically curtailed as there were others waiting to use the salt. Already EX219 had been packed away and shipped out. As far as EX181 was concerned it had been decided to concentrate on the 1506cc engine alone, which had by this time been installed in the car. Unfortunately, unable to wait any longer, Stirling Moss had already returned to the UK to honour a racing commitment at Oulton Park. So the driving was now in the hands of Phil Hill. With the surface still damp and slippery in places, Hill’s average speed for the mandatory two runs was a magnificent 254.33mph for the mile and 254.91 mph for the kilometre. The target had been achieved in spite of the wretched weather. The team could now go home in the certain knowledge that it had been a job well done. (To be continued).

Our thanks once again to Andy Knott, Editor Safety Fast, and author, Peter Neal, for their permission to reprint this article.