Working Inside the Octagon (Part 1)

When John Thornley was given the go ahead to put EX I75 (to become the MGA) into production at Abingdon he also managed to persuade his BMC directors to allow him to open a small design office there too. Set up in June 1954 with Syd Enever as Chief Engineer it would supersede the Cowley MG and Riley office located at Morris Motors which had, under Gerald Palmer, successfully engineered the ‘Z’ Magnette and the Riley Pathfinder, both by this time in production at Abingdon.

Two of its key personnel, Jim O’Neill (body design) and Terry Mitchell (chassis design), were immediately recruited by Syd Enever. Speed was of the essence where the new sports car was concerned, as Thornley wanted it in production by mid 1955. Jim O’Neill was immediately dispatched to Morris Bodies Branch in Coventry to take charge of the body engineering and work alongside their in-house draughtsman, Eric Carter. Their task was to lay down the body skin lines to pass over to the Pressed Steel Company who would be responsible for the necessary tooling and manufacture of the outer panels. As the bodies would be assembled (and painted) at the Coventry factory, it was decided that Bodies Branch would also be responsible for the manufacture of the internal body structure. These panels would be made mainly on fly presses, with simplicity (and cheapness) being the order of the day. Another young Cowley draughtsman by the name of Don Butler was recruited on loan to assist Jim and Eric with this task.

Back at Abingdon, Syd had found himself another talented young design engineer, Harry White, a suspension specialist from Morris Motors, who would assume the mantle of Chief Chassis Draughtsman. The return of Roy Brocklehurst from two years National Service in the RAF would complete the design team at this stage. It would be churlish not to mention as well the Specifications section with which they shared an office, comprising a team of five people led by Percy Lay, with Ann Crosby running the Print Room, all of whom formed an important part of Syd’s engineering team looking after, not just the MG models, but the Rileys too. Abingdon was of course also the home of Riley cars at this time.

Complementary to the design office (and equally important) was the Experimental shop. Under the auspices of Alec Hounslow and Henry Stone, two of Abingdon’s pre-war racing mechanics, this was a department very close to Syd Enever’s heart. It was here on the engine test bed that he’d spent many a happy hour coaxing inordinate amounts of horsepower from a variety of versions of Goldie Gardner’s successful record breaker EX 135. He now had the green light to expand this important aspect of his activities too, not just to enable him to cope with the demands of the new two-seater, but the additional workload required by a new record breaker programme, and also the preparation of racing and competition cars. Marcus Chambers had been brought in by John Thornley to run the competition side of things but at this stage had no budget to set up his own department. A number of new faces began to appear in Experimental: Jimmy Cox on engine build, welding specialist Harold Wiggins, skilled turner Reg Haddon, mechanics Cliff Bray, Doug Watts (brother of Syd Enever’s secretary, Isla), Tommy Wellman, etc, many of whom would go on to make a name for themselves in the future Competitions Department.

It was in this environment that I found myself in the October of 1954. I had applied for an apprenticeship at Morris Motors and having had an interview was waiting for the next intake when, out of the blue, I received a telegram to the effect that there was an opening at MG if I was interested. Things moved quickly after that and I soon found myself, a very ‘wet behind the ears’ 16 year old, signed up as an apprentice at the MG Car Company Ltd for five years to ‘learn the art of a draughtsman’ as it clearly stated in my indentures. My starting pay was two pounds four shillings and a penny a week whilst my lodgings alone were three pounds. Suffice to say I relied pretty heavily on parental funding to begin with.

After a few days in the office I soon found out what my true vocation was to be in these early days and months. The drawing office and experimental shop were on opposite sides of “A” building, which was the main assembly area. The two young girls in the office had apparently voiced their displeasure at being asked to deliver drawings etc., between the two locations. The route took them past the production lines and of course the men would whistle and call after them all the time. Although this was only good-natured banter, the girls found it extremely embarrassing and had put their foot down. My job then as the lad in the office was to take over this task to save them their blushes!

The volume of work at that time however dictated that I would also get to do some proper work as well. This mainly consisted of taking care of modifications to existing drawings and filling out the paperwork to go with the changes. Whilst somewhat boring, this was a good way of becoming familiar with production drawings and learning procedures. I also got to produce some performance graphs for the Le Mans cars as well as some simple detail drawings. Roy took me under his wing from the outset and helped me settle into my new and unfamiliar surroundings. I recall that one evening when we were leaving the office at finishing time, he showed me the MGA prototype, EX 175, which was kept under a dustsheet just below the stairs in a corner of “A” building. The production workers had all gone home and an eerie silence had descended on the factory. I still remember the thrill of seeing for the first time this streamlined two seater that was so very different from any MG I had ever seen before. The contrast with the TFs that were going down the line at that time was incredible.

By the end of the year Jim O’Neill had returned to Abingdon having handed over all the relevant information to Pressed Steel whilst Don Butler stayed on with Eric for another few months before returning to Cowley. Jim was able to move into an empty office next to the chassis office that had been vacated by Charlie Martin’s Production Control department. He was joined at this time by Denis Williams who had moved over from Radiators Branch. Denis had worked for Jim previously in the MG office at Cowley. As Jim was still spending a great deal of his time either at Pressed Steel, Bodies Branch or at one of the many supplier companies, I was asked to move into the body office to assist Denis. Under Denis’s expert guidance I was soon able to progress to assembly and installation drawings.

I remember the buzz of excitement when, in early 1955, the aluminium body shells for the Le Mans cars began to arrive at the factory. These were the first MGA bodies, albeit slightly modified for the race, that anyone at Abingdon had seen up to that point. In fact because of delays in the tooling process, which would in turn delay the car’s announcement, they would have to run at Le Mans under the experimental number EX 182.

At about this time we were informed that we would soon be moving to a new drawing office located elsewhere in the factory. This was largely as the result of John Thornley’s efforts regarding the setting up of a BMC Competitions Department within the Abingdon works. The budget for this allowed for the provision of a new facility which would also include the experimental shop. The project was being handled by MG’s talented young factory planning engineer (also ex-Cowley), Mike Inston. It just so happened that Mike’s office (that he shared with Jim O’Neill) was right next door to Syd Enever’s and Syd had managed to persuade him to include a new drawing office in the plans as well. Although Experimental had only been allocated a third of the floor space in the new building this was offset by the provision of a brand new engine test house, with space for at least two test beds, to be built next to the carpenters shop in the main yard. Mike had very cleverly integrated the drawing office into the new unit located at the northern end of ‘B’ block (now Oxford Engineering) by designing a cantilever style mezzanine floor into the roof space, along one side of the building. Despite proposals over the ensuing years to relocate us first to Longbridge and then to a green field engineering centre in the Midlands, this office would remain our ‘home’, substantially unchanged, until the factory closure at the end of 1980. Reasonably large by Abingdon standards, this new facility would allow space for both chassis and body departments to have two full size layout tables each, plus a number of individual drawing boards at either end.

Having settled into our new domain, new projects seemed to rapidly gain momentum. No sooner had the team of Le Mans cars left the factory than work began on a successor for I956. Coded EX 186 this would be a super streamlined racing car based on the MGA chassis and having a twin overhead cam engine and disc brakes. Using the basic shape of the I954 record breaker EX179, Jim O’Neill and Denis Williams evolved a body shape that was both functional and extremely attractive. The idea was to take the fight to the Porsches who were already beginning to dominate the one and a half litre class at that time. Sadly all work on this car came to an abrupt halt at the end of the year when the BMC board decided to withdraw from racing and instead concentrate on international rallying. Denis then moved on to oversee project EX 202 which was the six-cylinder ‘Z’ Magnette. This was a superb car to drive but while the only visual change was a wider radiator grille the structural changes required would rule it out on grounds of high tooling costs.

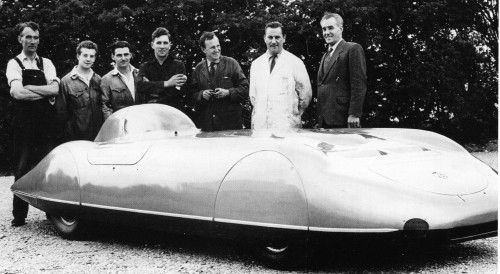

Meanwhile the chassis boys were formulating the new high performance twin cam, disc braked version of the MGA which, it was planned, would go on sale to the general public in limited numbers. Terry Mitchell was also working on the chassis for Syd’s latest record breaker project EX 181. Inspired by the incomparable George Eyston, a man who probably had more experience of record breaking than anyone alive at that time, the target was 250 mph from 1½ litres. A number of eighth scale models were made by Harry Herring, MG carpenter turned model maker, and tested in the Armstrong Whitworth wind tunnel at Coventry. These became known as Enever’s toys! The mid-engine configuration chosen, with the driver located at the very front of the car, gave it the appearance of being something of a scaled down version of John Cobbs’ successful Reid Railton designed pre-war land speed record breaker. This is hardly surprising when we know that Railton was consulted by Eyston in the very early stages of the EX 181 project.

By 1957 the design office had gained two new draughtsmen. Dickie Wright joined Harry White’s chassis team whilst Jim O’Neill added ex-Pressed Steel and Aston Martin body draughtsman, Don Hayter, to his small team. The department had also gained another apprentice in the shape of local lad, Bob Staniland. I welcomed Bob’s arrival if for no other reason that it meant that I could finally hand over my regular task of having to sneak out of the Cemetery Road gate and hot foot it down to a little shop in Spring Road with a pocket full of change to fetch Terry’s pipe tobacco!

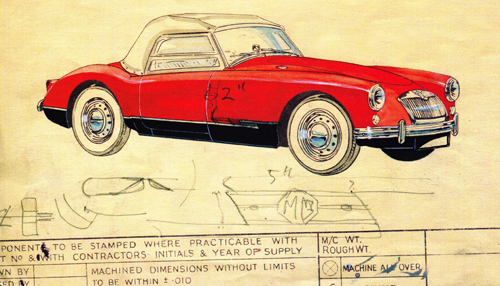

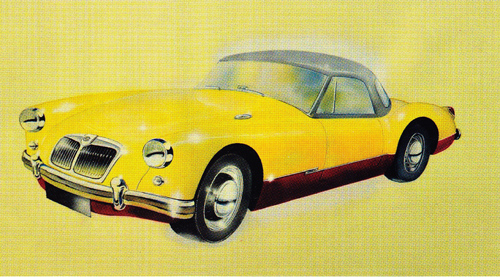

At this time Jim was also heavily engaged on the design and development of a hardtop for the MGA. At the same time, he needed to keep an eye on the work that Eric Carter was doing at Bodies Branch on the MGA Coupe. Because of Jim’s workload it was decided that Terry Mitchell should take on responsibility for EX 181’s body shell as well. With Jim and Denis pretty much ‘up to their eyebrows’, when Syd wanted some thumbnail sketches of possible two-colour schemes (which were then all the rage in America) for the MGA, I was lined up for the job. Syd didn’t say very much at that time, at least not to me so I assumed that he was satisfied with what I had done. A few days later Jim told me that Syd now wanted one of these sketches drawn up properly to a larger scale. He also informed me that Syd had ordered an Aerograph spray pen for me to work with. This operated using compressed air, so the factory maintenance department ran an extension airline up into the office from the development shop below, to which a reservoir was fitted to ensure a constant working pressure. The whole idea was making me decidedly nervous and I wondered whether a bit too much was being expected of me. I expressed these fears to Jim who countered with “just do the best you can”. The job was duly completed and delivered to Syd and I heard no more. The Aerograph pen was put away and things were soon back to normal. The idea of dual colour schemes was quietly dropped and didn’t resurface for a number of years and even then came to nothing.

Thank you to the MG Car Club and Pete Neal for allowing us to reproduce this article from Safety Fast magazine.