MG Comes to Abingdon Part 1

In the last article we left Cecil Kimber pondering the future of his MG Car Company. With the introduction of the Morris Minor based MG Midget he had unwittingly become the victim of his own success.

In the last article we left Cecil Kimber pondering the future of his MG Car Company. With the introduction of the Morris Minor based MG Midget he had unwittingly become the victim of his own success.

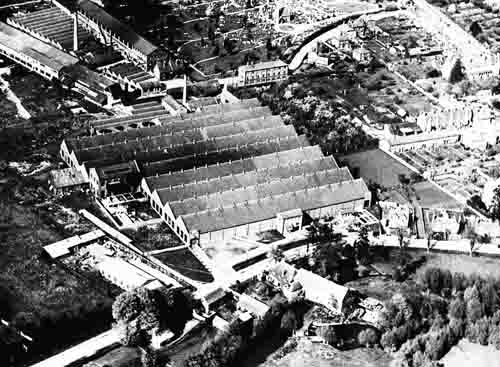

Edmund Road was now at breaking point. Even the acquisition of the old tram terminus building at nearby Leopold Street as a paint and body shop would not be enough to solve the problem. As well as heading up his own car manufacturing company, Kimber was still nominally responsible for the Morris Garages. This side of the business had also continued to expand, bringing with it its own set of problems. As a result, the Morris Garages had leased (with an option on the freehold) an unused part of the Pavlova leather works at Abingdon-on-Thames for the storage of used cars. Kimber decided that in spite of the extensive renovations that would be necessary, this site, with its large and relatively new factory building, would be the best solution for his expanding car business.

Edmund Road could then be utilised as the used car centre for the Morris Garages group. With the renovations completed, the move to Abingdon took place over the final months of 1929, with an inaugural luncheon being held on January 20, 1930, attended by the great and the good including of course William Morris. Kimber had no difficulty in persuading his management team to make the move to this new location.

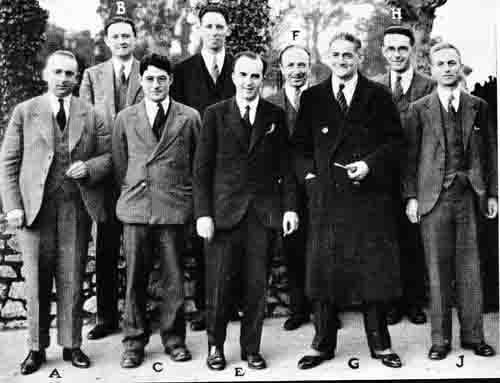

Messrs: (A) Muzzell, (B) Charles, (C) Colegrove, (D) Cousins, (E) Kimber, (F) Propert, (G) Lord Nuffield, (H) Maynard, (J) Pennock

Headed up by works manager George ‘Pop’ Propert, ably supported by Cecil Cousins overseeing production as well as the experimental shop, there were the likes of Ted Colgrove looking after sales, Messrs. Maynard and Vines taking care of purchasing, George Tuck responsible for publicity, with John Temple taking care of the service department. Somewhat surprisingly most of the workforce also opted to make the move in spite of being offered alternative jobs at the nearby Morris works. H.N. Charles, who had been assisting Kimber for some time on all matters technical, now joined the Abingdon management team as Chief Draughtsman. At the other end of the scale was a promising young mechanic who had transferred from the Cornmarket workshops by the name of Syd Enever who was put to work assisting Reg Jackson in the experimental department. Syd, as we shall see, would become a major player in the years to come.

The very fact that Kimber was building cars of a sporting nature made them attractive to those individuals who wished to take part in competitive events. For example an 18/80 was prepared at Edmund Road for Francis Samuelson to use in the 1929 Monte Carlo Rally. This was followed by the same factory preparing three Midgets for the Earl of March, Leslie Callingham and Harold Parker to drive in the JCC High Speed Trial at Brooklands that June. All three drivers gained gold medals on that occasion, as did two privately entered M-types. H.N. Charles’s first job when he arrived at Abingdon was to produce a road-racing version of the 18/80 to be known as the 18/100 (sometimes referred to as the Tigress). The body styling was reminiscent of the racing Bentley of that period (a marque that Kimber had always admired). Its first outing was to be the Brooklands 12/12 (24 hours over two days) in May 1930, in the hands of Callingham and Parker. A couple of hours into the race the engine ran its bearings and had to be retired. However, five Midgets were prepared for the same event with special bodies and revised camshafts. The cars ran faultlessly for the 24 hours and went home with the team prize. The factory followed this success by marketing a Double Twelve replica at £245. The 18/100 however failed to find a market with only five examples eventually being manufactured. This was not altogether surprising, given that the price had crept up to £795 at a time when the country was experiencing a serious economic depression.

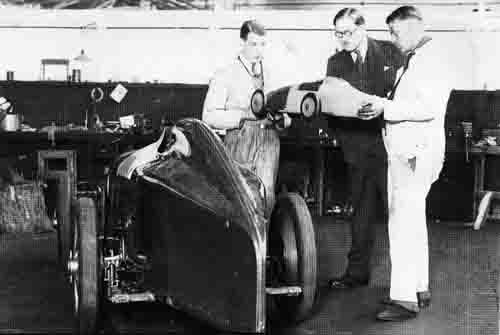

It can be seen from the foregoing that Kimber was rapidly being drawn into the motor racing scene. This was compounded when a young racing driver by the name of G.E.T. (George) Eyston, colleague Ernest Eldridge (a one time World Land Speed Record holder) and fellow Cambridge graduate Jimmy Palmes approached Kim in the summer of 1930 with the proposal to build a special car, using the Midget engine, with which to attempt to achieve 100mph with a 750cc car; something the Austin Motor Company had also been trying to achieve. Charles was already working on a new design of chassis frame, which had a three-inch longer wheelbase and was listed in the Project Register as EX 120. This was made available with Kimber’s blessing for Eyston’s record breaking project and Cousins was instructed to make Reg ‘Jacko’ Jackson available to build up the special car in conjunction with Eyston’s team. An area next to the experimental shop was partitioned off to provide a makeshift (but highly secure) race shop. An attempt was made to streamline the bodywork but it must be said that the appearance was functional rather than beautiful! Nevertheless it was the engine that was considered to be the important item and it was to this that Abingdon directed their energies. Although Eyston began breaking records with this car in December 1930 it was not until February 1931, on the banked circuit at Montlhery near Paris, that he became the first to put 100 miles into the hour with a 750cc motor car.

In the meantime H.N. Charles and his colleagues had been busy back at the factory designing a racing version of EX120 to be known as the Montlhery Midget or C-type. Remarkably, in the space of just two months 14 of these cars had been virtually hand built and readied for the Brooklands Double Twelve race meeting. The 12/12, in common with most of the races at Brooklands at that time, was run on a handicap basis and at the finish five C-types occupied the first five places. The Montlhery Midget would gain many more successes on the racetrack but more importantly its simple but effective chassis design would form the basis for all future two-seater MGs up to and including the TC.

The first production cars as such to feature this new design were the D-type four-seater, which utilised the M-type’s 847cc engine with its three-speed gearbox, and the rather more sophisticated F-type Magna (also a four-seater), which sported a six cylinder 1271 cc (basically Wolseley Hornet) power unit with a four-speed gearbox. Both of these models were offered in open and closed body configurations. Available from October 1931 both cars sold steadily but neither would repeat the spectacular success of the original Midget. To be fair this was the year in which the great depression had reached its height and even the M-type only achieved half of its previous year’s sales. The outcome was that MG ended the year making a small loss. A total of 1,354 cars had been sold against almost 2,000 the previous year. With sales of the M-type falling off rapidly, Kimber reasoned that a new two-seater, following more closely the specification of the C-type, might be the shot in the arm that was desperately needed. August 1932 saw the unveiling of the new Midget, designated the J2. With its 7ft 2in wheelbase, crossflow head, twin SU carburetters, four-speed gearbox and sporting a rather neat remote gear lever that would become a standard fitment on all subsequent MG sports cars, it was, at a basic price of £199.10s, outstanding value for money. Interestingly, an open four-seater and a closed salonette were offered on a similar chassis and designated J1 Midgets.

Thanks to these new models and with the F-type Magna sales picking up, Abingdon managed to sell some 2,376 cars in 1932, whilst making a healthy £25,000 profit. In the October of that year Kimber introduced a new chassis with a wider (4ft) track on a 9ft wheelbase. With a new six-cylinder 1087cc engine based on the current Wolseley Hornet unit, output was, however, a disappointing 38.8bhp. Its best feature without doubt was its pre-selector gearbox, controlled, not from the steering wheel, as was generally the case, but from a gear lever style remote control on the gearbox. Designated the K-Magnette, it was available initially with a four-seater pillarless saloon body. Although quite an attractive car with its long sweeping wings and sliding roof, this new MG was not a resounding success and it was quickly followed in February 1933 by long and short chassis two- and four-seater open versions. These too failed to capture the imagination of the buying public, influenced to some extent maybe by their somewhat high prices. The range was re-launched later in the year with a larger (1271 cc) engine but these too only managed to find a handful of customers. Earlier in the year Kimber (and Morris) had been persuaded by Earl Howe and his good friend Count ‘Johnny’ Lurani to build three special road racing cars to be entered as a team in the 1933 Mille Miglia. A great deal of pre-race testing was done over the actual course, which paid off handsomely with two of the cars finishing first and second in their class. Although the third car failed to finish, MG was nevertheless awarded the team prize, having outpaced, and more to the point outlasted, much of the opposition. These were of course the famous supercharged, 1087cc K3 Magnettes about which so much has been written.

Meanwhile George Eyston had been busy on the record breaking front. Even as he was achieving the magic 100mph with EX120, MG were busy building him another special car. Listed as EX127 – Single Seater Racing Car, it too would have the 746cc supercharged engine but this time the target would be 120mph; the even more magical two miles a minute. This time however the body was properly streamlined with just sufficient room to accommodate George’s large frame. By December 1932 and once again at Montlhery, with the car having acquired the name ‘Magic Midget’ Eyston had raised the International Class H record to 120.56. His personal mechanic and co-driver, Bert Denly would push this figure up to 128.62mph over the flying mile and kilometre in October 1933. Not bad for a 746cc supercharged version of the 847cc four-cylinder engine originally designed for a cheap and cheerful Morris Minor! At this point Austin retired gracefully from further record attempts.

Now that the K3 was available, Eyston was keen to move up a class and got the boys at Abingdon to build him a new record breaker based on the 1100cc engine and a K3 chassis. Looking like a scaled up version of EX127 it was officially known as EX135, but its distinctive brown and cream striped paintwork earned it the title ‘Humbug’ after the popular sweet of that name. On its first outing at Montlhery in October 1934, Eyston duly secured six records in class G. Although this would be Eyston’s only outing in this car, EX135 would become even better known (and take many more records) in the hands of another driver, more of which later.

Back to 1933 however. At the beginning of the year the Abingdon factory had updated the Magna range with the four-seater now designated the L1 and the two-seater the 12. Visually the main change was the use of the swept wings from the K-type. Under the bonnet, however, was to be found a new version of the K-series 1086cc power unit. This was a much-improved version of the Wolseley Hornet engine, which had been completely redesigned by Charles and his small team and actually gave more horsepower than its 1271cc counterpart. Whilst steady sellers, these cars sadly did little to really excite the buying public.

At the 1933 Motor Show Cecil Kimber announced a new two-door saloon on the L-type chassis, which he called the Continental Coupe. Describing it as an ‘ultra-fashionable town carriage in the best French style for the discriminating motorist’, it in fact proved to be the joker in the pack and because of its styling remained extremely difficult to sell.

The end result of this plethora of models that had been marketed by the company in 1933 (some 14 or 15 in all) was that the MG Car Company ended the year having sold a reasonable amount of cars but had slipped into the red once more, albeit by only a small amount. The reality however was that it had been the ever popular J2 that had accounted for almost two thirds of these sales, thereby just about keeping the Abingdon factory’s head above water.

Obviously aware that the two-seater Midget was the company’s bread and butter and fully realising that the J2 couldn’t go on forever, Kimber announced its successor in March 1934. One major problem with the J2 had been its rather vulnerable two bearing crankshaft. lt liked neither sustained high rpm nor too much load at low speed. Broken crankshafts were becoming something of an embarrassment at Abingdon so chief designer Charles and his Wolseley counterparts came up with a brand new three bearing 847cc engine, which whilst giving marginally less horsepower than its predecessor was a much sturdier and thus more reliable power unit. This new Midget, to be known simply as the P-type, slightly larger than the J2 and a little more comfortable, had lost nothing in the looks department and at £222 represented excellent value for money.

This new Midget was quickly followed by a new Magnette, the N-type, which in effect replaced both the K Magnette and the L-type Magna. With a new and rather more sophisticated chassis frame and sporting the redesigned KD engine, it represented good value at £305 for the two-seater and £335 for the four-seater.

1934 also saw the launch of the Q-type two-seater racing car. An amalgamation of many K3 and N-type components, it sported a supercharged P-type engine reduced to 746cc fitted with a pre-selector gearbox. The Zoller supercharger enabled the engine to give some 100bhp in standard trim (using special fuels) and it’s something of an understatement to say that the car became rather more than a handful when driven at high speed!

1934 had been a better year for the MG Car Company, having produced an £18,000 profit, most of which had been derived from the ‘P’ and ‘N’ types. Things were, however moving fast in the motor industry and Kimber and Charles were aware that independent suspension systems were beginning to appear on many Continental cars.

Next time we will look at how they planned to face up to this challenge and how unforeseen events would head the Company in an entirely new direction. To be continued…

Our thanks once again to Andy Knott, Editor Safety Fast, and author, Peter Neal, for their permission to reprint this article.