MG Abingdon – A New Beginning Part 1

The Bonneville Salt Flats (originally lakes) have only a small window of opportunity when they are dry enough for record breaking activity. The new MG record breaker, EX179, was due to make its runs in August/September 1954 leading to some fairly frantic activity at the Abingdon factory to get the car ready in time.

The Bonneville Salt Flats (originally lakes) have only a small window of opportunity when they are dry enough for record breaking activity. The new MG record breaker, EX179, was due to make its runs in August/September 1954 leading to some fairly frantic activity at the Abingdon factory to get the car ready in time.

Right in the middle of this, BMC management, as the result of some pretty serious lobbying both from Abingdon and the US dealer network, relented and gave the go-ahead to project EX175 or DO 1062 as it would now become. As with the Z Magnette, the new 2-seater would use the BMC 1500cc B-series engine. John Thornley had also pulled off another master stroke: the Abingdon design office would re-open to support the engineering of the new car, with Syd Enever as chief engineer.

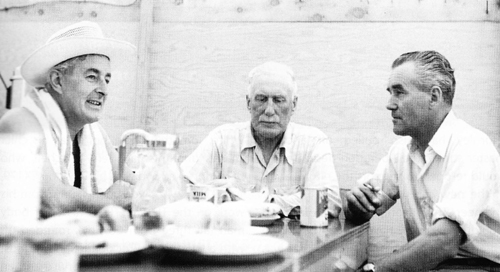

This meant, of course, that Syd would of necessity have to stay behind in Abingdon whilst the new record car was being put through its paces in the USA. It would nevertheless be in the capable hands of George Eyston and John Thornley with Reggie Jackson standing in for Syd as technical advisor. Syd’s new drawing office consisted of all of five design staff: Harry White, something of a ‘boffin’ as his chief chassis draughtsman, Terry Mitchell, who had impressed Syd with his work on EX179, Jim O’Neill who Syd already knew from his work on the TD and TF, as his chief body man (all three from Cowley), rounded off with a young Roy Brocklehurst, having just returned from his National Service and an even younger, budding apprentice (yours truly), as gofer! Syd, of course, already had his small experimental shop under the leadership of Alec Hounslow and Henry Stone, which had so recently been responsible for building EX’ 79.

Jim O’Neill was immediately dispatched to Morris Bodies Branch at Coventry to work alongside Eric Carter, their in-house designer, to finalize the body lines before presenting them to Pressed Steel who would be responsible for making the press tools and manufacturing the panels for the new car. Thornley’s main headache was that there was insufficient tooling money in the budget for both a new chassis and a brand new body shell. As Syd had already committed the lion’s share of the budget to his new chassis, Thornley had to find a way to resolve the body issues. As luck would have it, Pressed Steel were keen to get what they saw as a high profile project so agreed to look at how they could reduce the cost of tooling. They were already looking at a new system of rubber/plastic tools for low volume requirements, and felt that this might be a possible option for the new MG. They had also agreed that if this idea proved to be unsatisfactory they would shoulder part of the tooling costs themselves and amortize them into the piece price, which is precisely what happened at the end of the day.

Over on the salt flats, Eyston and his co-driver Ken Miles, took EX’ 79, with its experimental un-supercharged 1466cc XPAG engine, out onto the 10 mile circuit virtually straight out of the box and after a couple of warm up laps and driving in three hour shifts, circulated regularly and without any problems at around the 125mph mark. Having thus established 7 international and 24 American National class F records, between 250km and 200km, including the 12 hours, the team felt they could afford to relax a little. The next day the sprint engine was installed and the car rolled out on the salt once again. With Ken Miles at the wheel, EX’ 79 broke the 10 mile flying start international class F record, which was achieved at a mean speed of 153.69mph another good day’s work.

Meanwhile in Abingdon the small design/development team was forging ahead with the new car. As a stopgap measure the 1466cc version of the XPAG engine was put into production. Now known as the XPEG it was duly installed in the TF which now carried the label ‘TF 1500. Although this move failed to impress the motoring press, it did help to boost sales of the Midget in America, even though the increase in horsepower was relatively small. Perhaps more importantly, it bought Abingdon just sufficient time to get the new car into production.

As the result of Pressed Steel’s abortive attempt to get the new car’s cheaper tooling to work, the production date for its introduction had to be delayed. This required John Thornley to change his plans for the cars unveiling. It had been arranged for the new 2-seater to be announced to the public in June 1955. By way of achieving maximum publicity for this event the plan was to enter a team of two or three cars in the Le Mans 24 hour race to coincide with its introduction.

The Le Mans cars were instead moved to the prototype category and given the label MG EX’ 82, being the next available number in the EX register. Four cars were built in total having aluminium skin panels: two had been accepted for the race with the third as reserve and the fourth going as a spare/practice car. All four cars were driven from Abingdon to the Sarthe circuit by the mechanics who had helped build them. They were accompanied by a specially designed transporter which would act as a workshop, kitchen, sleeping quarters and storage unit for the team, which was being led by recently appointed Competitions Manager, Marcus Chambers.

Things did not go exactly to plan as just before the first change of drivers Dick Jacobs lost control at White House corner and ended up in a ditch. The car caught fire and though Dick was thrown clear he nevertheless sustained serious injuries. After many weeks in hospital he made a good recovery but sadly never raced again.

Once back at Abingdon the design team began to make plans for the following year’s Le Mans 24 hour race. Work began on a new racing car based on the MGA chassis and twin cam engine, but with a far more streamlined body. This project as given the experimental number EX186 and the plan was to sell them in strictly limited numbers, thereby qualifying them as production cars for the purpose of the race. Unfortunately, after just one more outing with the remaining EX182 cars (the TT at Dundrod in Northern Ireland), BMC cancelled all further racing activities in order to concentrate on rallying. This would be the responsibility of the newly formed BMC Competitions Department, also located at Abingdon. EX186 was put on the back burner at this point.

With the body tooling completed the new 2-seater was quickly put into production as the MGA and very soon began beating all previous production records. In fact some 13,000 MGAs were manufactured in its first full year of production. Although the chassis members were made by a specialist company, they were assembled in the press shop at the Abingdon factory as had been the case with most of the previous models of MG. In this instance, however, there was a great deal more welding required than previously, putting the small teams of skilled welders under constant pressure to meet production requirements.

Although a factory hardtop was quickly made available, John Thornley was still keen on the idea of marketing a fixed head coupe version of the MGA. The challenge, as ever, was that there was onIy a very small budget available for its manufacture. Undeterred, Thornley and Enever hatched a plan whereby Morris Bodies Branch would virtually hand build these tops with simple presswork being limited to the more complex items such as the windscreen pillars. The manufacture of these roof assemblies was entrusted to Midland Sheet Metal who then shipped them to Bodies Branch, where they were welded on to suitably modified tourer bodies. Here, they also fitted the windows, door locks and latches etc, so there was little in the way of trim work required once the bodies arrived at Abingdon. It is interesting that the Coupe featured a wrap around windscreen which was current fashion at the time, and something that Syd Enever was very keen to include.

In the early part of 1955 word was that a new engine was being developed for MG. As more information filtered through it transpired that it was not so much a new power unit as Abingdon had hoped, but a heavily modified version of the B-series unit. The main feature was the new aluminium twin-camshaft head with hemispherical combustion chambers. The camshaft drive from the crankshaft was a two stage affair using both gears and a duplex chain. Although the ‘Twin Cam’ version of the MGA would not be marketed for a further three years, the Company immediately saw an opportunity to develop this engine for record breaking. Thus it was that EX179 was fitted with a prototype twin-cam engine (unsupercharged) and readied for an attempt on the Utah Salt flats in August 1956. It is interesting to note that whilst the capacity of the later production engine would be 1588cc the early version used in EX179 was only 1489cc. It is also interesting to see that in spite of the problems that beset this power unit in production, the record car ran trouble free on this occasion for 12 hours at an average speed of 141.71 mph and achieved a maximum average speed of 170mph over 10 miles.

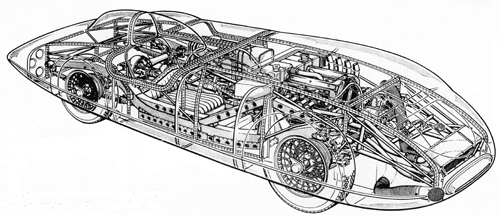

This however proved to be just a curtain raiser for the main event. Eyston and Thornley had managed to get approval to build yet another record breaker with which to attack the sprint distances up to 10 miles. The whole idea was to garner as much ‘free’ publicity as possible in a country where conventional advertising, on an across the board basis, was an extremely expensive option. Now it was over to Syd Enever and his team to come up with a suitable design. The car would again be powered by the 1489cc B-series twin-cam unit but this time it would be fitted with a powerful Shorrock supercharger to help give the engine the kind of output that would be required to reach the target figures that they had in mind. The body shape too would need to achieve optimum aerodynamic performance, not only to enable the car to reach the kind of speeds envisaged but to also keep the car on the ground and in a straight line. Reid Railton was one of those consulted for his considerable experience in the field of racing and record breaking and it was agreed that the best configuration would be to position the engine amidships driving the rear wheels with the driver sitting immediately in front, positioned over the front axle, in a semi-reclining position.

One limiting factor in reducing the height and width of the car and therefore achieving the minimum frontal area was the size of the wheels. Dunlop Ltd undertook to develop a 15 inch wheel to carry a tyre having a maximum diameter of 24 inches diameter having just 1mm of tread. Terry Mitchell was given the task of designing a brand new tubular chassis frame to which he added MGA type front suspension, with a de Dion rear suspension to his own design. Terry was also eventually given responsibility for the body which was based on perfect aerofoil sections in both plan and elevation. All of the wind tunnel testing, incidentally, was carried out using ¼ scale wooden models.

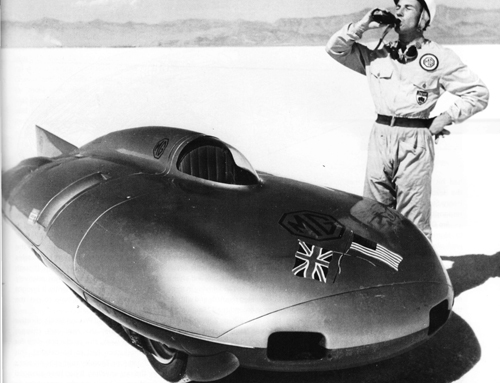

Stirling Moss, as an already internationally known motor racing star, had been engaged to drive the car in America in August 1957. The aim of the exercise was to achieve 250 mph over the flying mile and kilometre. The whole thing was nearly a disaster, as just before Stirling’s arrival at Salt Lake City, a severe storm had left the salt flats flooded. He and the team waited for almost a week for the salt to dry sufficiently for an attempt. Finally, by late afternoon on the day before he was due to leave for another engagement the salt was deemed to be just about dry enough for a run. One end of the course was still under water, so its effective length was reduced from 14 to 11 miles overall, ruling out the 10 mile distance. In fading light and on the still damp salt, in a car that he’d never driven before, Moss recorded an average speed of 245.64mph for the flying kilometre, and 245.11 mph for the mile; a quite remarkable achievement given the circumstances.

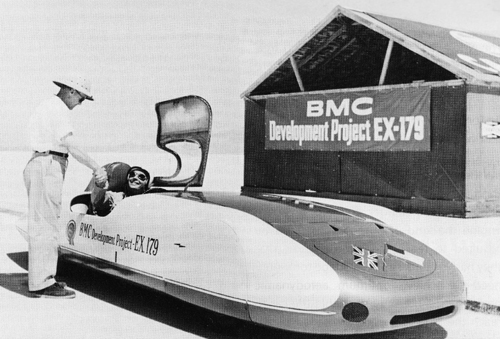

For good measure the team had also taken along EX179 now known as ‘BMC Development Project EX179’. This had been fitted with the BMC 948cc A-series engine as used in the Morris Minor (another car that the Corporation was trying hard to sell in the USA). Driven by David Ash and Tommy Wisdom it picked up three international and 50 American long distance records in Class G, whilst three days later they bagged a further clutch of records with a supercharged version of the same engine.

All this talk of racing and record breaking might give the impression that there was not much of interest going on at Abingdon on the production side of things. In point of fact there were major changes on the way. 1957 saw MGA sales breaking all records for MG with 20,571 cars off the line. The ZB Magnette was holding up nicely at just under 7,000 units produced. The Riley Pathfinder was being phased out to be replaced by the Riley 2.6 and production of the new Riley 1.5 was starting up there too. After the first 150 cars were built, however, production of the new small Riley saloon was moved to Cowley, to make way for a new departure for the Abingdon plant. The big news was that production of the Austin Healey 100/6 was being moved from Longbridge to Abingdon which meant that from now on the MG factory would be the home for all future BMC sports cars. There were even rumours of yet another new sports car coming their way… (to be continued).

Our thanks once again to Andy Knott, Editor Safety Fast, and author, Peter Neal, for their permission to reprint this article.