MG Abingdon – Changing Times Part 1

During the 1960s, the Abingdon engineering department worked on three new, but each quite unique, projects. The first of these had its roots in the 1950s as EX220, the Jim O’Neill Mini based 2-seater sports car. (Pictured is Sir Alec Issigonis at his desk in Longbridge).

During the 1960s, the Abingdon engineering department worked on three new, but each quite unique, projects. The first of these had its roots in the 1950s as EX220, the Jim O’Neill Mini based 2-seater sports car. (Pictured is Sir Alec Issigonis at his desk in Longbridge).

This would carry over all of the Mini’s major mechanical components, fitted to a cheap and cheerful 2-seater bodyshell, thus reviving the basic premise of the original M-type, which would be marketed as a replacement for the Sprite and Midget. As soon as Alec lssigonis got wind of what MG were up to, he decided that his own Longbridge project team would take over responsibility for this venture. This, in fact, had the effect of pretty well killing off the project, as lssigonis felt that creating a 2-seater Mini, would, in some way, dilute the basic principle of the Mini package.

By the mid-1960s the idea was revived once more when the BMC management decided to once again consider a replacement for the Spridget, and allocated the project number ADO34 to cover its development. This time, however, it would be a rather more refined car, albeit still utilising Mini components (front and rear subframes, transverse engine and gearbox driving the front wheels, etc), but with body styling by Pinin Farina. lnterestingly, ADO34 reverted at this stage to 10 inch wheels: Jim had originally specified 12 inch for EX220 to give the car a more ‘grown up’, proportional, appearance.

The second project, EX234, was an entirely different kettle of fish. This was a design for a sports car that was initiated entirely by Abingdon. Once the MGB was in production, Roy Brocklehurst, Syd Enever’s chief chassis draughtsman, was made project engineer and given the task of producing a brand new 2-seater that would sit somewhere between the Midget and the MGB. The chassis would be of monocoque construction with the engine located at the front, driving the rear wheels in the traditional manner. The suspension would, however; be entirely independent and utilize the Hydrolastic principle that had recently been pioneered by lssigonis on the BMC 1100 range of cars. Roy would work in conjunction with Alex Moulton on the suspension design and it was hoped that as it didn’t impinge too much on the Mini/1100 design, there wouldn’t be too much resistance from Alec lssigonis. Once again, after an initial body design exercise by Jim O’Neill, Farina was given the task of styling the car.

Before we discuss the third project, ADO21, it is important to consider what else Abingdon had on their plate at this busy time. Obviously, whilst it was important that the engineering department should be looking to the future, keeping the current production cars abreast of the mounting pressure from regulations being dreamt up, in particular by the Americans both at State and Federal level, was their first priority.

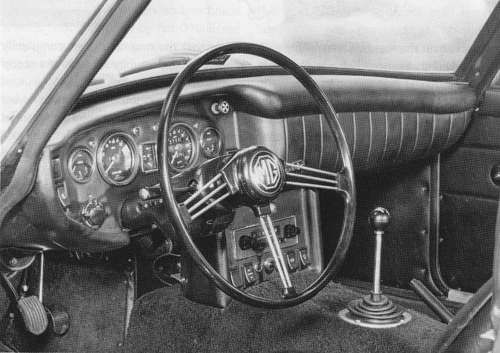

At the end of 1964, Roy Brocklehurst had been given the additional role of Assistant Chief Engineer in preparation for Syd Enever’s eventual retirement. From the mid-60s onwards, however, Roy would find himself spending the lion’s share of his time dealing with and interpreting the US safety regulations. ln February 1968, John Thornley circulated a memo to all his managers and supervisory staff stressing the importance of meeting these requirements. “lt is vital” he wrote, “to our future success, that everyone realises the need to maintain the standard of our cars, not only to meet the safety requirements, but also to safeguard our reputation as manufacturers”. When one considers the scope of the regulations, from windshield defrosting to controls, occupant protection to fuel tanks, it’s quite remarkable that existing sports cars like the MGB and particularly the Midget could be made to comply. ln the case of the requirement for a padded fascia for instance, there were no existing examples to work from so Abingdon’s design and technical development teams, Ied by Jim O’Neill and Mike Hearn respectively, were having to face an extremely steep learning curve. Also, because of the time required for tooling they had to hope that the “off tools” parts would perform in the same way as the prototypes. Another challenge was that everything that was being developed for the MGB had to also be replicated in a slightly different way for the Sprite and Midget. Many sleepless nights ensued before everything finally came together!

Apart from meeting the safety standards, which affected almost every aspect of the car, it became a necessity that from January 1, 1968, all vehicles exported to the United States should meet the requirements of the clean air act. ln order to meet these strict emission measures in the short time available, Longbridge and Engines Branch had put their heads together to develop a system utilising an air pump fitted to the engine to control the carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons in the exhaust gasses. As compliance was the responsibility of the manufacturer, it was necessary to test the cars before they left the factory. To this end a £60,000, purpose built testing laboratory was provided at Abingdon, manned by a staff of five under the leadership of Mike Allison. As this was a completely new operation, Mike decided on a one-in-ten sampling procedure, assuming that if these all passed, the ones in between would also be OK. After the initial batch of cars had been dispatched, Mike was summoned by the US authorities to witness these being tested on the dockide after being unloaded at Long Beach in California. He was happy to be able to report that all of the Abingdon cars had ‘passed’ the test. However, Triumph and Jaguar reps were less than happy to be told that their cars had a failure rate of 60% and 90% respectively! Even some of the domestic manufacturers had failed to achieve Abingdon’s 100% success rate!

One of the victims of these complex regulations was, of course, the Austin Healey 3000. The car would have required a major redesign and although this was considered, neither the money nor the will was forthcoming from BMC at that time. The phasing out of the big Healey was a major blow to the Competitions department with whom it had enjoyed great success.

Looking for another big beast to rally, ‘Comps’ had begun to consider the MGC as a possible successor to the Healey. They soon realized that the car as it stood would simply be far too heavy to give them any chance of success. After the 1967 Sebring race (the only circuit race they were authorised to compete in) and with Peter Browning now at the helm (Stuart Turner had handed over the baton at the beginning of the year), the decision was made to order six lightweight aluminium bodied cars. Syd Enever’s department was recruited to assist in persuading Pressed Steel Swindon to make the necessary panels. This was quite a major headache for them as the presses would need to be reset in order to press the panels in alloy and then of course put back again afterwards. lt is an example of the goodwill that existed between Swindon and Abingdon at that time that they were willing to undertake this task.

A set of panels was then dispatched to Morris Bodies Branch in Coventry to be assembled onto the steel underframe. Bodies Branch also added the wheelarch flares, for the larger wheels and tyres, which would become such a defining feature of these cars. Geoff Clark from the Abingdon development shop recalls being dispatched to Coventry one day with all the relevant hardware to check the wheel clearances before the body was painted and signed off. The first prototype was completed before the MGC was actually announced to the public and so it was fitted with a Sebring MGB engine (with the capacity increased to 2,004cc giving approximately 150bhp) and entered in the May 1967 Targa Florio. Entered in the prototype category, it is surprising that no-one seemed to notice that the car was quite different to an MGB under the skin. It seems that the motoring press completely missed the opportunity for a bit of a scoop on this occasion!

The Competitions department were not quite finished yet, as they also wanted aluminium cylinder heads (and later, blocks) for these cars. lt was once again left to Syd Enever to do a bit of arm twisting at Engines branch to enable this to happen! The Targa Florio car was subsequently fitted with the six cylinder engine (race modified with an aluminium head) and entered in the March 1968 Sebring race, driven by Paddy Hopkirk and Andrew Hedges. lt was after this event that these special aluminium bodied MGCs gained the sobriquet GTS (S for Sebring).

The all-alloy engine was fitted to the second of these cars to be built and entered in the 1968 Marathon de la Route held at the Nurburgring. The two cars were also raced again at Sebring in March 1969. Whilst the cars ran well and showed great potential it was all to no avail, as the new British Leyland management decided, in their wisdom, to shut down the Competitions department as a cost saving exercise.

ln February 1968 it was announced by Longbridge that Alec lssigonis had asked to be relieved of his executive responsibilities within the operational and administrative sphere of BMC engineering. He would, however, continue in the role of Technical Director in order to concentrate on long term research projects. ln his place as Director of Engineering would be another ex-Morris Motors man: Charles Griffin. Better known as Charlie Griffin he was well known to the engineering staff at Abingdon as he had been in charge of the experimental road testing department at Cowley prior to the Austin/Morris merger. There was a hope that he might therefore be rather more disposed towards MG than his predecessor. Unfortunately there was scant time to find out as the merger with Donald Stokes’ Leyland Group occurred just three months later.

As a result of the merger the car side of the business was split into two groups: Austin Morris and Specialist Cars. Abingdon would henceforth find itself in the Austin Morris side of the business. There were many who were critical of this move, feeling that MG should have been included in the Specialist Car group. Viewed in retrospect however, it is doubtful whether Abingdon would have survived as long as it did, had this been the case.

Once the merger had taken place and things had begun to settle down, it became clear that Stokes felt that there would only be room for one corporate sports car in the line up. With both MG and Triumph in need of a new model it was agreed to let both design teams work on their own ideas for a replacement initially. Don Hayter was ordained as Project Engineer in place of Roy Brocklehurst, whose time was now being taken up almost exclusively by the welter of regulations coming out of America.

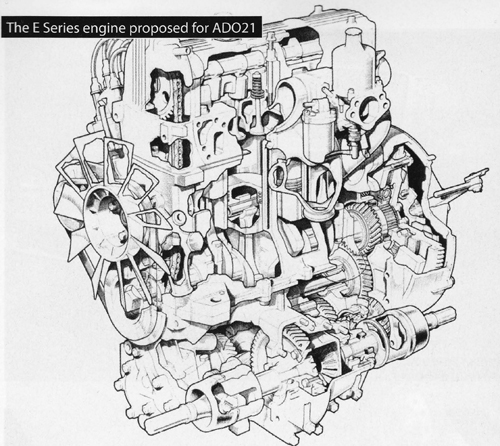

The new Austin Morris project coded AD021 would be mid-engined, using a version of the new 4-cylinder overhead-cam E-series engine designed specifically for use in the new BMC designed, British Leyland adopted, Austin Maxi. Don would design a new body/chassis unit in conjunction with Longbridge stylist Harris Mann, whilst Terry Mitchell and his small team at Abingdon would develop the suspension and engine installations. An MGB GT bodyshell was requisitioned and the development shop began to chop it about in order to install the transverse engine, positioned slightly in front of the rear axle line. A de Dion tube (what else!) was then installed forward of that (just behind the heelboard) linking the wheels, and the suspension units, consisting of vertical coil springs enclosing telescopic dampers, were located in turrets inboard of the rear wheelarches. The (12V) battery was positioned for convenience behind the engine with the radiator kept in its original location at the front of the car and the spare wheel taking up the space where the engine would normally have been. This set-up was adopted mainly to get the vehicle on the road as a means of developing the car’s rear suspension characteristics. Undoubtedly there would have been many more changes before AD021 ever got anywhere near production. It’s fascinating however to compare this mid-engine layout to that of the MGF which would proudly take its place in the MG line-up some 20 years later.

In July 1969 the factory suffered another shock to the system. This was the announcement that John Thornley, so much a part of the Abingdon scene, would be taking early retirement at the age of 60. Having survived some pretty major surgery over the previous couple of years, he had decided that he no longer had the energy to fight MG’s corner under the new regime.

All was not lost however, as he would be leaving the capable Les Lambourne, his former deputy and a much younger man, at the controls. Les had begun his career with Morris Motors as an engineering apprentice, rising to Assistant Works manager before transferring to MG in 1958.

Two more events would follow in quick succession before the end of the decade. The first of these was the closure by the British Leyland management of all inhouse magazines and car clubs within the corporation. This signaled the end of the company sponsored Safety Fast! magazine and worse, the closure of the MG Car Club office that had been located in the factory from the beginning of the 1930s. That the Club managed to survive this hiatus owes much to John Thornley and a small group of dedicated Club members.

The second and perhaps more serious of these events was, as already mentioned, the announcement, in the Spring of 1969, that the Abingdon based BMC (and latterly British Leyland) Competitions Department would close with more or less immediate effect, thus bringing to an end a proud tradition of participation in motor sport that had seen the department grow from humble beginnings to achieving repeated success in some of the world’s greatest and toughest car rallies.

Whilst sales of their cars continued to hold up, especially in the North American market, MG found themselves entering the 1970s with a degree of trepidation and wondering how long they could continue to build cars at Abingdon as part of what appeared to be a seriously Triumph biased Corporation.

Our thanks once again to Andy Knott, Editor Safety Fast, and author, Peter Neal, for their permission to reprint this article.