The “Black Mamba” MGA Coupe Twin Cam

Africa’s black mamba (Dendroaspis polylapis) is widely considered the world’s most dangerous snake. It can grow up to 14 feet, is lethally venomous, and highly aggressive when threatened. They are fast, and strike with lightening speed.

Africa’s black mamba (Dendroaspis polylapis) is widely considered the world’s most dangerous snake. It can grow up to 14 feet, is lethally venomous, and highly aggressive when threatened. They are fast, and strike with lightening speed.

It is appropriate, therefore, that a fast South African MGA racecar was named “Black Mamba”. The story of this car is told by Stuart Grant and includes its modifications, its race history, its accidents, and its rebuilds.

“The hooter blasts, the flag drops and the hush explodes into a deafening crescendo of sound as thirty-odd cars embark on an endurance test of man and machine lasting three-quarters of the way around the clock. This is the electric atmosphere of the start of the Rand’s Nine Hour Race, one of the premier motor sporting events in the country.”

This quote, found in Ken Stewart and Norman Reich’s iconic book “Sun on the Grid” perfectly sums up the romanticism of the famous endurance events that we generally associate with Kyalami. This type of gruelling event format was in its South African infancy when the 9 Hour kicked off but it soon grabbed the attention of spectators and competitors alike.

Stuart Grant catches up with the Protea Triumph and Black Mamba, an MGA Twin Cam, that both enjoyed remarkable success in these early days.

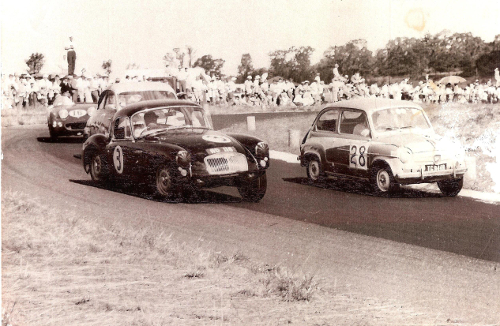

In 1956 the first South African 6 Hour Endurance Race was held at Pietermaritzburg’s Roy Hesketh circuit, but for the masses 1958 was the year South African endurance racing started in earnest. The biggest challenge laid out was to the two-wheeled fraternity with Grand Central (in today’s Midrand) hosting a 24 Hour. For the four-wheeling crews Hesketh still held the 6 Hour, Cape Town’s Killarney put on a 3 Hour and the first ever 9 Hour took place in November at Grand Central. With cars sporting names most of the public knew, heated on-track action and the excitement of hurried pit stops, there was always something on the go for the spectators. And the introduction of an Index of Performance award meant that even the humblest of cars could take home some silverware, so the teams and drivers arrived in bulk.

One such entry to the 1958 Hesketh race was a Triumph TR2 with John Myers and John Mason-Gordon at the wheel. Thanks to its low-revving reliability, reasonable speed and decent handling, the pair finished the race second behind the Horse Boyden/Alec Millea Alfa Romeo Sprint Veloce. Inspired by this result, they set out to improve the car. To them this meant keeping the TR2 reliability but shedding a few kilograms and moving the engine down and back a touch to make the car corner better. Myers had, of course, already designed South Africa’s first production car, a tubular-framed sportscar with fibreglass body, so was adept at the design and construction of what was needed to reach the goal. In August ’58 he sketched the plan of attack.

Into a tubular Myers frame went a TR2 rear axle with coil springs, trailing arm and a Panhard rod. Propshaft, gearbox and engine also came courtesy of the Triumph. So too did the likes of the gauges, pedal arrangement, master cylinders, front disc brakes and rear drums. Steering and front suspension came from Ford. The former being an upside down 100E Ford Prefect steering box because it offered less lock-to-lock (at 1.5 turns) than the Triumph, while the latter used a 1940s Ford CWT commercial van axle. Of course this wasn’t left standard though and Myers cut down the centre and welded some eyes onto it to act as swingarms, located by compression struts that ran backwards to the chassis. True to the plan, the engine was mounted as low and as far back as possible relative to the wheelbase.

To clothe the new creation Myers favoured aluminium over fibreglass. Mason-Gordon called for a narrow streamlined rear. Myers had a Dinky Toy Jaguar D-Type. They put pen to paper with these two references calling the shots and gave the sketches to Geoff Collins, who hand-built the body. The car was finished in April 1959 and immediately driven by the two down to ʼMaritzburg to compete in the 6 Hour. The race started at 14h30 and the Protea Triumph took up the lead, a position it held until the 20h30 finish, with the only real glitch being a mid-corner fuel surge that cut the engine mid-corner and sent the car on a slight off-track excursion into a verge. The car returned to the pits to top up the fuel and inspect damages before carrying on to win.

Second on the podium went to George Mennie/Dave Wright (No. 8) and Gordon Henderson/Clive Mitchell (No. 3) in a brace of MGA Twin Cams. Number 8 was a locally-built roadster while No. 3 was an early imported coupé finished in black paint.

Enter Black Mamba, mentioned earlier, and the restored car pictured today with the Protea.

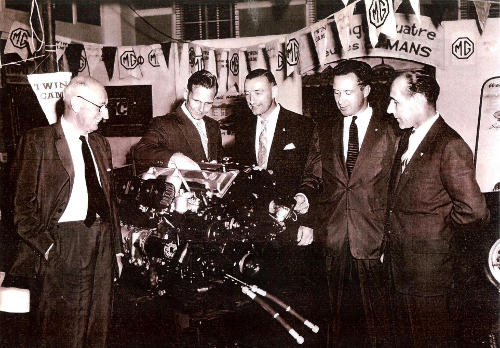

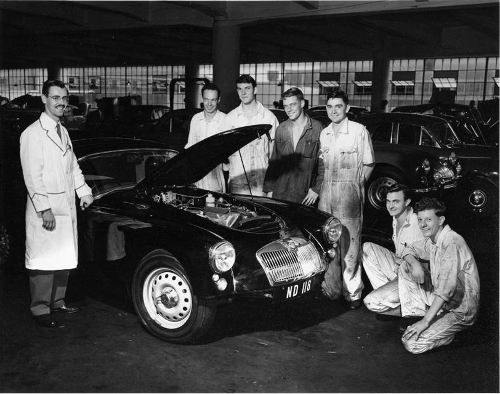

Black Mamba, sporting the chassis number YM2 554, was one of the first batch of four Twin Cam coupés built at Abingdon, England between June and September 1958, and was shipped with a full range of factory optional extras to Noel Horsfield, the managing director of McCarthy Rodway, the main MG agents in Durban. It was registered as ND118 on local plates and pressed into action as a dealer demonstrator, in the lead-up to the sale of the locally-built Twin Cam roadsters, which started at Motors Assemblies in February 1959.

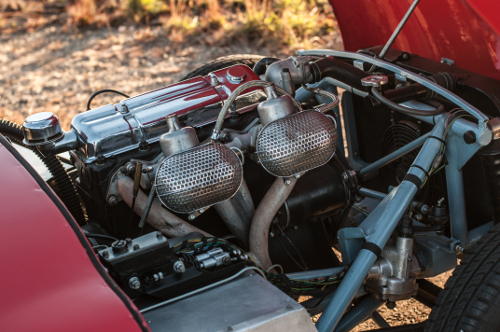

Like the Protea Triumph, Black Mamba’s racing career kicked off at the March 1959 Hesketh 6 Hour. It wasn’t the only MGA Twin Cam though, with three SA-built MGA Twin Cam roadsters in the hands of privateer outfits joining the party. McCarthy competitions manager, Mike Compton, led the preparation of the car, which included the removal of trim panels, heater, luggage rack, radio and bumpers. A close-ratio gearbox, competition oil cooler and competition shocks were added and various other modifications like a straight through side-exit exhaust, twin fuel fillers and a larger fuel tank found a home. The MG factory supplied a special Lucas D3AH4 distributor and a set of 2-inch SU HD8 carburettors.

Following a series of tests, a mixture of six parts aviation fuel, six parts premium petrol and one part union spirit (ethanol) was deemed to be the best for performance. Track time the week before the race revealed a misfire between 6000 and 6200rpm, which was then cured by the fitment of a Minor 1000 ¼ tonne truck distributor and setting the timing to 3° at top dead centre.

Following this test the name Black Mamba was applied – according to Bobby Olthoff, who prepared and raced number 7, due to the sound and speed the YM2 554 made.

According to Compton’s post-race notes, victory for Black Mamba looked likely for the first three hours as it tussled with the Protea and the number 8 roadster. But it wasn’t to be as a ruptured brake line meant an unscheduled stop for a replacement, and a loss of 10 minutes relegated the car to third by the time the flag fell on the 6 Hour mark.

After the event Black Mamba was returned to road specification by McCarthy but it did enter the 1960 Hesketh event, finishing seventh. Sadly, on the way back from the event, it was involved in a fatal pedestrian accident. The damage to the right-hand side was repaired and the race engine was replaced with standard Twin Cam engine. The car was then sold and subsequently disappeared and was not seen for many years thereafter.

As an out-and-out racer the Protea’s career carried on longer. Shortly after the ’59 6 Hour win, the Sports Car Club of South Africa nominated Mason-Gordon and the Protea, along with Ian Fraser-Jones (Porsche Spyder) and Bill Jennings (GSM Dart Porsche), to represent the country at that year’s Angolan Grand Prix in Luanda. Up against the likes of a Ferrari Testarossa, Cooper Monaco, Jaguar D-Type, Porsche 550 and a few of Maseratis, Mason-Gordon finished seventh and Jennings ninth.

Mason-Gordon recalled reaching 5700rpm at the end of the long sea front straight, which was scary because he never normally revved it past 5000 (he and Myers believed in racing as slowly as possible) but also because the calculated speed was 137mph, which you somehow had to scrub off enough to take a 90° right. Chris Fergusson borrowed the car for the 1960 East London 2 Hour where he finished third. Red Whitehouse bought the car and achieved some class successes leading up to the 1961 9 Hour – now moved from Grand Central to the purpose-built Kyalami. Whitehouse never got to drive in the race as his co-driver Pierre du Plessis rolled it at Jukskei during practice.

Following a rebuild Ivan Weitzman bought and campaigned it before selling it to Jan van der Merwe, who raced it in historic racing events in the early 1980s. The Zwartkops Raceway proprietor purchased it 1982 and after years of badgering he moved it on to Triumph fan Alan Grant in 1995. Grant continued racing the car until a minor accident necessitated a rebuild. And as is life with a competition car, another prang in 2008 resulted in yet another restoration exercise, which was completed just in time for the 2017 Knysna Hillclimb.

Various enthusiasts started searching for Black Mamba in the ʼ90s but it only surfaced in 2003, lying around in poor shape in Krugersdorp. The identity was confirmed by the stamped chassis number 554, the body number 61754, the competition oil cooler, the original black colour, various body modifications, and the ignition and door key number FP731, which was recorded by Mike Compton in his practice notes. The new owner, Bo Giersing, carried out a full restoration with the cherry on top being the fitment of SU HD8 carbs and the original engine (16G202) – found in Durban last year.

In an amazing twist of fate and alignment of the stars, these two cars reside within just 2km of each other today. Even better is the fact that soon the recreation of the complete 1959 Hesketh 6 Hour podium will be possible as Giersing is nearing the completion of the George Mennie Twin Cam.

NAMGAR wishes to thanks Stuart Grant and www.classiccarafrica.com for permission to reproduce this article. Photography by Etienne Fouche.