MG Abingdon – Final Days

Encouraged by the then government, it was the intention that the merger in 1968 between British Motor Holdings (BMC/Pressed Steel/Jaguar) and the Leyland Motor Corporation (Leyland/Triumph/Rover) would help to strengthen the remains of the British motor industry against the increasing competition coming from both Europe and Japan.

Encouraged by the then government, it was the intention that the merger in 1968 between British Motor Holdings (BMC/Pressed Steel/Jaguar) and the Leyland Motor Corporation (Leyland/Triumph/Rover) would help to strengthen the remains of the British motor industry against the increasing competition coming from both Europe and Japan.

In fact, the newly formed British Leyland Motor Corporation would, over the ensuing decade, prove to be a spectacular failure. The reasons were of course many and varied, but suffice to say that a combination of weak management and headstrong trade unions combined to ensure that the new corporation failed to produce, in adequate numbers, the kind of vehicles that the buying public wanted or indeed needed.

There were a few bright spots along the way; the much-maligned Marina, introduced hastily in 1971, was one. It sold in the kind of volumes that would go a long way towards keeping the company’s head above water. The Allegro, designed as a replacement for the BMC 1100/1300 range and introduced two years later didn’t have the kerb appeal of its predecessor, and never reached more than half the previous model’s annual sales figures in the UK market. The Princess too, introduced in 1975, whilst having more style than the BMC 1800 that it replaced, never really improved on the sales figures of its rather boxy looking predecessor.

By 1975, the company, now renamed simply British Leyland, was rapidly running out of cash. This resulted in the company having to be bailed out by the incumbent Labour government. At this stage the government held virtually all the company’s shares, effectively making it a nationalized industry. At this point Lord Stokes was moved upstairs to become President, with Lord Ryder; Chairman of the government’s National Enterprise Board who had previously written a report on the state of British Leyland, now assuming the chairmanship of the company.

Unfortunately Lord Ryder’s rescue plan, involving in the region of 1 billion Pounds of taxpayers’ money, depended on the complete cooperation of both management and unions, neither of which was forthcoming under his leadership. After a period of some two years it was obvious that things were not improving and his sudden resignation cleared the way for the appointment in August 1977 of Michael Edwardes, a tough industrialist who had made a name for himself running the Chloride Battery Group, as chief executive of British Leyland. By the beginning of February 1978, Edwardes had worked out what was needed for the company to succeed and issued a 15-page document outlining his plan to all managers and employee representatives.

The gist of it was that as centralisation had clearly not worked he would be splitting the company into a small number of separate enterprises to enable them to operate unhindered. The first of these, BL Cars (the name Leyland had become so toxic that it was being dropped altogether apart from the Truck and Bus Division), would be subdivided into three further companies, Austin Morris Ltd, Jaguar Rover Triumph Ltd and BL Components Ltd. It was not made clear in the document where MG would be positioned: in fact it was only mentioned at all on the last page as something of an afterthought. A further document issued by the chairman on the same day informed the management that Ray Horrocks would assume control of Leyland (sic) Cars with immediate effect.

Wasting no time, Horrocks issued a memo regarding sports cars, making clear his disdain for this part of the business. The strengthening of the pound against the dollar (largely as the result of North Sea oil beginning to come on stream) had in his words “made an already unprofitable business even more unprofitable”. This, he said, “has forced us to abandon our plans to introduce the ‘Lynx’ model (a TR7 based successor to the Triumph Stag) and to re-think our Sports Car strategy”.

Discussing the closure of the Speke No2 factory in Liverpool, he remarked that “it would probably be commercially prudent to discontinue TR7 completely”, but added that there was a need to stay in the market until “new models come in”. Once again there was no specific mention of MG. However, a memo issued as a follow up to the plant visit by Horrocks to Abingdon in May suggested that he had mellowed somewhat. The memo listed a number of his comments to questions that had been put to him. He confirmed that the company would stay in the sports car market, and said that he recognised Abingdon’s consistent performance and acknowledged that Abingdon and the MG name would continue. He also made the point that he supported MG Abingdon’s plans to celebrate their 50th anniversary.

Later in the year Michael Edwardes issued a memo to all employees in BL Cars. This addressed the issue of the unofficial tool room group who were threatening to call a strike throughout the car manufacturing operations. It was pointed out that this would put a number of plants at risk, and in particular Cowley, Abingdon and Canley. These factories were identified probably because they relied upon the supply of bodies from the Pressed Steel plants at Cowley and Swindon, which were the ones most affected by the toolmakers’ dispute.

It was nevertheless chilling to see Abingdon identified in this way. Fortunately the planned strike was averted and it was once more back to business. The next thing Abingdon received was an official communique on September 19 to the effect that MG had been transferred to the Jaguar Rover Triumph division of BL Cars. The argument was that as JRT Ltd were responsible for all car sales in North America; it made sense for MG to be part of that organisation. Plant Director Peter Frearson also saw it as a positive move. “I believe we will be encouraged to become more independent, flexible and outward looking,” he said, “evidenced by our position . . . reporting directly to the Managing Director of Rover Triumph”. His optimism wasn’t particularly shared by a motoring writer in the ‘Times’ newspaper who mused that “only time would tell as to whether the move was to develop MG, or eventually rationalise it out of existence”.

A brief memo was circulated confirming that the MG plant now featured in the five-year plan as one of the four principal Jaguar Rover Triumph assembly plants. Abingdon were nevertheless left wondering why the MG name couldn’t also be included in the company title – after all there were only two letters…. The other piece of information included in the memo was that with the phasing out of the Midget towards the end of 1979, the Vanden Plas Allegro would be assembled at Abingdon.

Hardly was the ink dry on the changes to the British Leyland group when in May 1979 the country was faced with a new administration. Not only was the new government Conservative but for the first time Britain had a woman prime minister. Margaret Thatcher was a lady in a hurry: not only did she intend to reduce the power of the trade unions, she didn’t like state owned industries either. Michael Edwardes, awarded a knighthood in the Queen’s Birthday Honours, was tasked with drastically pruning British Leyland in readiness for its sell-off to the private sector or at the very least to reduce the company’s dependence on government money.

He had two years in which to achieve this aim. Factories would need to be closed, non-car businesses such as Aveling Barford and Prestcold sold off and the workforce reduced by at least 25,000. A four-page statement was issued on September 10 outlining these proposals. Whilst Edwardes cannot be blamed for the timing of the document, indeed he may even have held it back until after MG’s jubilee celebrations, his management team must be held accountable for the appalling manner in which the news was released. Printed by the Nuffield Press at Cowley with the intention that every employee should receive a copy, it was distributed in such a haphazard manner that whilst some people received it in the morning, some like Abingdon didn’t see it until late afternoon by which time the details had been leaked from other parts of BL. The first some MG production workers knew of it was when they were interrogated about it by reporters from Radio Oxford and the ‘Oxford Mail’ as they left the factory. Even plant director Peter Frearson hadn’t had any prior warning.

The announcement regarding MG was blunt and unacceptably brief. “The effect (of the streamlining programme) would be to cease car assembly at Canley and Abingdon. Abingdon would be converted to become an extension of Cowley to enable the Cowley modernization programme and therefore model introductions to be accelerated. We would retain the MG Marque”.

So, all the assurances that Abingdon had been given over the years meant nothing. The feeling among the workforce from shop floor to senior management was one of utter disgust. Their loyalty, their hard work, their achievements, their total domination of the American sports car market all counted for nothing. The only ray of sunshine in this gloomy atmosphere was that production of the MGB would continue for another year. At least this would give everyone a chance to think about their future.

The other piece of news was that MG was to be unceremoniously dumped back into the Austin Morris group. Perhaps that ‘Times’ correspondent had been right to be cynical. The ‘O’ series programme was cancelled immediately as was any other work on the Abingdon models other than that required to meet legislation.

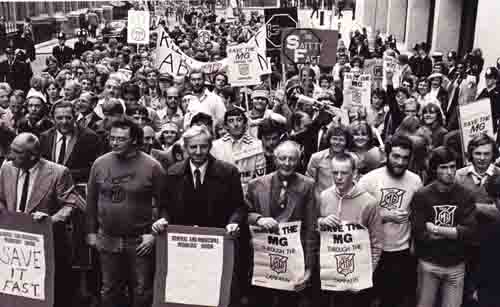

The news of Abingdon’s impending closure sparked off a huge debate in the media with everyone expressing sympathy for the demise of the MG brand, now assuming the status of “national treasure”. A protest march through the streets of London was organised by the MG clubs in conjunction with the trade unions with the theme of “Save the MG”. A petition was handed in to British Leyland headquarters at the end of the march by Jean (Kimber) Cook, Cecil Kimber’s youngest daughter. A debate was even held in the House of Commons on the fate of the company. Sadly none of these efforts had any effect. A plea by the American dealer network for a change of heart, partly orchestrated by John Thornley, was also unceremoniously kicked into touch by Sir Michael Edwardes.

Hardly had the ink dried on the Edwardes plan when two Canadian businessmen (Messrs Lalonde and Mason) flew to London with the idea of purchasing the MG factory and continuing production of the MGB. Their plan was to set up a kind of workers’ cooperative with money coming from private equity. After discussions with the government it became clear that BL had no intention of selling either the factory or the MG brand.

Next in the frame was a private consortium led by Alan Curtis, co-chairman and managing director of Aston Martin. They too wanted to keep the ‘B’ in production at Abingdon but with the benefit of a facelift to bring it up to date. Their plan was to eventually engineer a completely new state-of-the art replacement for the MGB designed to bring the marque back into profitability. Once again the major stumbling block was the fact that Sir Michael Edwardes had no intention of selling the brand. He was however coming under increased pressure from the government and the press to show more flexibility. As a result he relented and agreed to sell the factory and allow the consortium to use the MG brand under licence. Unfortunately this wasn’t enough to secure the necessary financial backing and despite a herculean effort by Curtis and his partners the deal fell through.

There was of course massive disappointment at Abingdon and a realisation that this really was now the end of the road. There was however one last project awaiting the Abingdon engineering department. It did not have an EX number nor even an ADO number, simply the code name “Bounty”. Under a shroud of secrecy the staff were issued with their instructions.

They would act as liaison engineers for a brand new model that would be put into production at Cowley. This was of course the much-vaunted product of the collaboration arrangement that Edwardes had set up with the Honda Motor Company. The advantage to BL was that they would get a fully engineered vehicle and tooling at a bargain price. Intended as a replacement for the Marina, both the manufacturing of the body shell and vehicle assembly would take place at Cowley with engines and associated hardware being shipped over from Japan. The engineering team soon became aware that the model they were dealing with was the Honda Ballade, which carried over a large number of well-proven Civic components. The Abingdon team saw a certain irony in the fact that the car they were responsible for would be badged in the UK as the Triumph Acclaim!

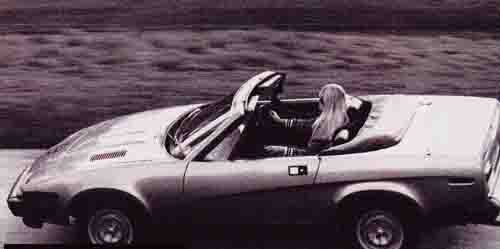

Just before the announcement that the MG factory was to close, BL released details of their new Triumph TR7 two-seater convertible destined for the American market. On paper it was quite a nice little sports car: 2-litre slant-four ohc engine, 5-speed manual transmission, reinforced body shell with its lowered rear deck line and boot lid making it better looking altogether than the coupe. Priced at just under $8,500, JRT expected to sell some 25,000 of these cars across the USA per annum.

There was only one problem. It wasn’t an MG. The American sports car buying public voted with their feet and simply walked away from this latest offering from BL. As time went on, and despite heavy discounting, the US dealers struggled to shift them in any appreciable numbers and by 1981 the company, its sports car strategy in tatters, decided to cease production of its flagship sports car. This left just Jaguar and Land Rover to carry the banner in the United States, a market pioneered by MG back in the heady post war era and undeniably a market that they had come to regard as their own.

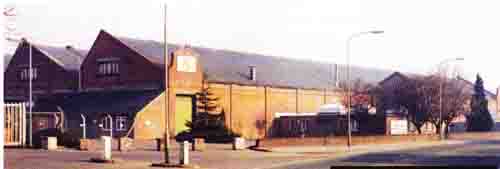

In the light of subsequent events most observers tend to agree that the closure of the MG factory and the abandonment of one of the most popular sports cars of all time was, from every point of view an extraordinarily flawed decision. Abingdon is still awaiting its apology.

Our thanks once again to Andy Knott, Editor Safety Fast, and author, Peter Neal, for their permission to reprint this article.